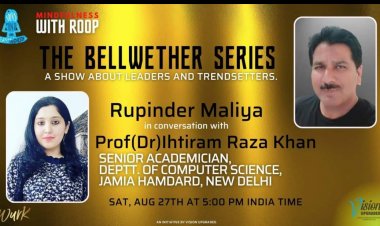

Jack Thompson, a famous video game crusader, still has a grudge

Jack Thompson was kind enough to answer his phone on a sunny Friday afternoon in South Florida. It only took a few minutes for him to unleash a salvo of takes, forever cocked and loaded for anyone willing to listen.

At age 70, the infamous attorney hasn’t changed his mind about violent video games

When the video game industry is valued at $300 billion, a Halo TV series trailer is occupying prime real estate during the AFC Championship, and a GTA facsimile like Free Guy is one of the top-grossing films of the year, it is clear that Jack Thompson lost the fight. For those who don’t remember, Thompson was the attorney who led the charge against violent video games and helped morph a fringe topic into a dominant wedge issue of the mid-2000s. He has since vanished from the public eye as the outrage ran dry, and everyone moved on.

Looking back, the imagery of the zeitgeist — think Joe Lieberman brandishing a light-gun live on CSPAN or Hillary Clinton equating first-person shooters to tobacco and alcohol — is rendered strange and atemporal in the harsh light of the 2020s. Yes, the affair still earns some perfunctory attention, usually engineered by the NRA in response to yet another mass shooting, but I think everyone who was once involved in the gaming panic knows that the jig is up. Degenerate classics like Mortal Kombat, Doom, and Grand Theft Auto seep deeper into the marrow of our culture with each passing day with no real objection from the nation’s lawmakers. Hell, Rep. Madison Cawthorn, one of the young stars of the MAGA movement, is actively petitioning for American military technology to better resemble the arsenal in Halo. Where have all the true believers gone?

Thankfully, Jack Thompson was kind enough to answer his phone on a sunny Friday afternoon in South Florida. It only took a few minutes for him to unleash a salvo of takes, forever cocked and loaded for anyone willing to listen. He asserts an association between the rise of crime in New York City to Take-Two, the publisher behind Grand Theft Auto. After all, he explained, Take-Two is headquartered in Manhattan. Thompson is never going to betray his heart, for better or worse.

“Americans are famous for moving on,” he told me. “We have the attention span of a mosquito. Churchill said that when most people stumble across the truth, they pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and move on as if nothing happened. What pissed people off about me is that I didn’t do that. I’m 70. I’m still here. I haven’t died yet.”

I believe I first became acquainted with Jack Thompson in an ancient issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly. I was 14 years old and proudly self-identifying as a gamer. To be fully ensconced within that community in the early 2000s, one was encouraged to hold a special hatred for a litigious attorney in Florida who had filed numerous grievances against the games industry. The cases were usually built around the specious premise of a depersonalizing psychological force that trained impressionable teenaged PlayStation owners to commit random acts of violence. In eighth grade, I did not possess any ethical grounding beyond one core thesis: those who wanted to take my video games away were the enemy. Thus, for a large portion of my youth, there was nobody I hated more than Jack Thompson.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23301361/0000003296.jpg)

The breadth of Thompson’s portfolio is impressive and almost impossible to recount in full. He’s a career moral agitator; before video games, he attempted to restrict the sale of 2 Live Crew albums, and he has a longstanding feud with Howard Stern. But Thompson’s life changed forever in 1999 when he filed his first gaming lawsuit, claiming that the perpetrator of the Heath High School shooting was desensitized by a collection of computer games. (MechWarrior, Resident Evil, and Redneck Rampage, to name a few.) That case didn’t go anywhere, but it put Thompson in a prime position to pounce on the burgeoning hysteria that would soon swallow up the then-forthcoming Grand Theft Auto III. Rockstar’s opus was gruesomely sculpted out of futuristic 128-bit tech and possessed an unapologetically nihilistic spirit. In an age where video games had not yet fully assimilated into mainstream society, the levy was destined to break.

“It made me sick to my stomach,” said Thompson when I asked about the first time he saw Grand Theft Auto up close. “I was in my house, I put [Grand Theft Auto III] in a video game console, and it was disturbing. You weren’t passively watching something; you were participating in it.”

By the middle of the decade, Jack Thompson had filed lawsuits targeting nearly every tendril of the video game supply chain. He sued Best Buy after claiming that his 10-year-old son purchased a copy of Grand Theft Auto Vice City from a store clerk. (Best Buy affirmed its existing policy to only sell M-rated games to those 17 or older.) He sued Take-Two on multiple occasions, usually in conjunction with some sort of homicide trial involving underaged gamers. (All were dismissed.) He became histrionic, almost revivalist, in his allegations, fashioning himself as a modern-day crusader.

Thompson once postulated that the DC sniper was a radicalized gamer, based on the fact that investigators found a Tarot card inscribed with the words “Call me god” at one of the crime scenes. (“You go to video game chat rooms, and you have the proclamation ‘I am God’ all over the place,” he said, on a 2002 episode of The Today Show.) After the release of Bully, a 2006 game set in a Northeast preparatory school, Thompson discovered that the male main character had the ability to kiss another boy. “We just found gay sexual content in Bully,” he wrote in a letter to the ESRB. “Good luck with your Teen rating now.” (The board responded, saying they were already aware of the scene when rating the game.)

Thompson’s relentlessness, charisma, and cosmic belief in his cause made him a fixture on the cable-news salon circuit. He has sat down with Chris Matthews, Glenn Beck, and Rebecca Quick and was once prominently featured in an episode of 60 Minutes. The message boards I regulared were speckled with primordial Jack Thompson memes, casting the man as the singular existential threat to the hobby I loved. It feels strange to say this in our era of millionaire Twitch streamers and international esports leagues, but for a period of time, you could make the argument that Jack Thompson was legitimately the most famous person in video games. Over the phone, Thompson allows that maybe, some of that fame went to his head.

“I enjoyed being the center of attention. We’re all egocentric to a certain extent. To be on cable news, to do 60 Minutes, to be on Opera … it’s fun,” he said. “It’s a rocket ride. But eventually, you come back down to earth.”

Thompson was disbarred by the Florida Supreme Court in 2007 after being accused of 31 different lawyerly violations. The charges are bleak and include allegations like sending “hundreds of pages of vitriolic and disparaging missives, letters, faxes, and press releases,” and “publicly accusing a judge as being amenable to the ‘fixing’ of cases.’” Thompson has not practiced law since, and he still regards the disbarment as a devastating derailment of his video game activism. Does he admit guilt? Not really, though he does have some regrets. Thompson believes he was too angry when dealing with his adversaries, which encouraged them to play hardball with him in return. But overall, I get the sense that Thompson believes he is a martyr of his convictions. Nobody is ever going to convince him that he wasn’t in the right.

“The plan was to disbar me so I wouldn’t be relevant, and that by and large happened,” he says. “It was a terrible experience. … You can be a felon in Florida and get your law license, but you can’t be Jack Thompson and ever get it back. Even if I had an epiphany that everything I did was wrong, and that I was a scumbag, and that I’m sorry, that doesn’t result in any remedy.”

The irony is that Thompson’s wish is coming true. In many ways, he’s finally getting the congressional scrutiny over video games he’s always petitioned for — though not in the form he imagined. In 2019 the FTC held a workshop centered around loot boxes, the pernicious, habit-forming scheme designed to drip-feed randomly assorted new items into players’ inventories in the hopes that they’ll keep spending money for more. The World Health Organization concurred with those anxieties when it added video game addiction to its list of diseases that same year. For the first time in my life, there is a groundswell of momentum to ethically regulate the predatory economic practices of the games industry. Thompson and I both agree that publishers need to keep kids safe, but he has not abandoned his fundamental principle that a violent video game might entice troubled kids to commit violence themselves. That leaves him permanently out of step with mainstream cultural and scientific momentum. If only he knew the revolution was already upon us.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23301344/ss_c8f0c20768412066cd1e182705b14d26acc4beb0.jpg)

Thompson anticipates a reckoning. Someday, he says, the defense team in a murder trial is going to argue that their client was revved into a frenzy due to, in part, an inveterate video game habit. The jury will buy it, and the suspect will escape the death penalty. At last, all of Thompson’s warnings come home to roost, and the real villains — Tommy Vercetti, Niko Bellic, and Carl Johnson — will be unmasked for all to see. It’s hard for me to even conceptualize the scenario that Thompson describes, but I suppose that anyone still committed to dismantling Grand Theft Auto in 2022 must engage in some degree of magical thinking.

“It’s going to work, and that’s going to get people’s attention,” said Thompson. “People are going to freak out. They’re going to say, ‘Wait a minute, somebody can kill somebody and only be convicted of manslaughter by virtue of a video game defense?’ … [they’ll want to] do something about the games and their distribution.”

But until that day comes? Who knows. Thompson is considering writing another book but was slowed down two summers ago when he had a heart attack after teeing off on the first hole of a round of golf. “I had a 100 percent blockage in what’s called the Widowmaker artery,” he said. Thompson’s moral alignment has also evolved in realms outside of the video game business in some surprising ways. He’s a proud evangelical Christian and tells me he voted for Trump in 2016. “It became pretty clear that was a big mistake,” he said. Thompson re-registered as a Democrat in 2020 and voted for Joe Biden in the Florida primary. People can change, even Jack Thompson. “We’ve all been affected by Black Lives Matter and what happened in Minneapolis,” he said. “There’s no reason to trust the Republican party anymore about anything… I think they’ve completely screwed up by hitching their wagon to Trump.”

In fact, I think it is safe to say that Jack Thompson is at peace. He’s retired, he’s playing golf every day, and he only relitigates the culture war when a journalist calls him up on the phone. Thompson holds onto one longshot; maybe, someday, he’ll be reinstated to the Florida bar. “I don’t want anyone’s apology, but I have this hope, this unshakable idea. That’d be a nice thing,” he said toward the end of our conversation. Perhaps the last Grand Theft Auto crusader can pick up where he left off, and a brand new generation of gamers can hate his guts.

“I’ve got everything I need,” finishes Thompson. “Except more time.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by Leader Desk Team and is published from a syndicated feed.)